Smacks

I spoke with Devin Borgwardt about his various bike crashes, racing in Berlin, and maintaining KOM's across Florida.

Devin was 17 years old, living in Bradenton, Florida, when his brother introduced him to fixed-gear cycling. “My brother was a big drift guy. He and his friends loved fixies. They got me into it, but then they became uninterested pretty shortly after. I stayed doing it.” Devin rode bikes as a child, but it didn’t become a hobby until he learned to ride a fixie. “I picked it up pretty quick. I wasn’t a sporty kid. I played basketball growing up, and stayed fit, but I wasn’t really athletic. It wasn’t until I started riding bikes that I realized that the way I’m built really worked for cycling.”

A component of fixed-gear cycling that appeals to Devin is the control he feels over the bike itself. “I don’t have the same handling on a road bike that I do on a fixed-gear. I’ve always felt safer on a track bike because of that. The track bike is more responsive to my intent with what I want to do.” He added that he can stop more effectively on a track bike as well. “Maybe it’s just how my brain works. I hop, and I bang my wheel against the ground. I could be going 20 to 25, two or three bangs on the ground, and I can be stopped in a track stand.”

When he first started riding fixed, Devin rode solo because there was no bike community in Southwest Florida. “It’s really car-centric. I did it alone for years. I built maybe five bike scenes there over the course of ten years. People around me started to ask about bikes, I started to get them interested, and they’d get a fixie.”

The bike scenes that Devin attempted to build in Florida ultimately died out as people became less interested, as his brother had. “It had waves where they’d start to do it, and then they’d become disinterested. Five separate times, there were five to twenty people interested, and we were doing group rides. Some of them were getting fast. Some of them just wanted to do the casual stuff. It never really took off. I was always the sole person trying to push that community there.”

The infrastructure in cities like Bradenton and Sarasota, where Devin would ride, made it difficult for a cycling community to form. “It’s primarily roads with 40 to 60 miles per hour speed limits. Everyone’s doing 10 to 15 over. There’s no bike lane on these roads, but they’re really wide, so you can really surf and take wide angles. That’s what I did for a long time.”

Another element that made it difficult for Devin to build a lasting cycling community in Florida was the hostility of the motorists. “Florida drivers are very angry and resentful to begin with. On top of that, they see you do anything that they deem wrong; they’re very vengeful and vindictive. I have run stop signs and heard tires burning out behind me from a car that’s driving 45 miles an hour through a neighborhood to try to catch me. I’ve had cars follow me up on sidewalks.”

Despite all the challenges presented to Devin, he persisted and formed some unexpected feuds along the way. “Sarasota has a really rich Mennonite/Amish culture, but it’s very condensed into a one-square-mile radius in the middle of Sarasota. I’ve taken so many people on ‘Welcome to Sarasota’ bike rides, and as soon as we get into the Mennonite center, they are always looking around at the people on their hand-welded bikes with their hand-sewn clothes, and they’re like, ‘Where are we? What are we doing?’”

The conflict arose when a Mennonite family noticed that Devin had built a lengthy list of KOM segments on Strava. KOM stands for King of the Mountain, and is awarded to the leader of a user-created segment on the app. The user with the fastest time stays atop the leaderboard, but is subject to losing that placement if somebody completes the segment faster than them. “There was this group of people in Sarasota, they were all Yoder’s. Yoder is a real common name amongst them, if you’re not familiar. There were these two dads, Jeff and Brian Yoder, I think. They had a son each, and the four of them would get together and lead each other out for only my segments. For two and a half years straight, we had this nonverbal rivalry.”

The competition between Devin and the Yoder family intensified quickly. “I would get a segment sometimes, and the same day, an hour or two later, they would go and get it. After a year of this, I started scrolling through their starred segments. They were watching me. They all had 20 to 30 of my segments starred and no others. All of their rides were centered around KOMs. Honestly, they were all world tour, pro-level fitness. If they went for my segment, chances are, they got it. We went back and forth. Some of them, we traded six, seven, eight, nine, ten times each.” Devin explained that friends have reached out to him, telling him that the leaderboards between him and the Yoder family require such a high level of fitness that they are practically unattainable for anyone else who wants to try to snatch them.

This competition was heated, but it was never mean-spirited. “They’re kind enough people, but we had this really fun rivalry where I could tell that it was very competitive from their end. I don’t want to say that I rage-baited them, but I would comment on their rides like, “You couldn’t let me have it for just an hour?” They would never reply or speak to me, but they would reply to other comments that were like, ‘Congrats on the KOM.’ I clearly bothered them, and it took nothing for me to poke at them.” All things considered, this competition motivated Devin to keep riding. He was averaging 100 to 200 miles per week and developing his ability to ride fast.

Devin’s passion for riding fast inspired him to get involved in racing. Alleycats became his first foray into competition. “When I got into bikes in 2013, most alleycats were happening in Tampa, St. Pete, Gainesville, and Miami. It was a very small handful of us that were really pushing for that. I spent some years racing, then as I started racing less, I started organizing more. I really enjoyed organizing.” Devin’s favorite aspect of organizing these events was bringing people together. Unlike New York City, the concentration of racers in Florida is much less dense. “Every city is a three-hour drive apart, so race day is big. You get to see all these people that you never see throughout the year.” Devin explained that he did about 20 alleycats over five years in Florida.

In 2017, Devin started participating in track criterium races, or track crits. “The scene in Florida never really did take off, so the track crits there were unsanctioned. They were just added onto a road crit as a last-minute thing that no one paid attention to. Usually there’d be eight to maybe twenty guys lining up. I did that for some years.”

The first crit that Devin raced in was thrown by his friend Matt. “He organized maybe three crits over the course of a year in this really quiet neighborhood in Gainesville, around a massive neon green, algae-filled pond. It was a cool course.” Devin made the podium for the two crits he did in Gainesville. Eventually, he continued to race for the crit scene that was developing in St. Petersburg during the mid 2010s and early 2020s.

In 2020, Devin was recruited to a cycling team called Rush. Joining the team enabled Devin to race outside Florida. “Rush was able to send me around a little bit more to some of the bigger fixed-gear crits. I did Mission Crit for three years straight.” Rush originated as a messenger company based in South Florida, but evolved into a racing team. As Rush grew their roster, they reached out to Devin. “They were trying to expand their fixed gear focus. They reached out to me like, ‘Hey, we noticed that you raced some unsanctioned crits. Would you like to race for us?’ I was pretty quickly like, ‘Yeah.’ It was a pretty good situation. They had some frame sponsorships, they had some kit sponsorships, and it really facilitated getting me into the sport. They helped lower the barrier to entry for me to actually start racing.”

In 2023, Devin was allowed to travel to Berlin to participate in Rad Race, a series of short track races on go-kart tracks. This was an exciting experience for Devin, as he comes from German ancestry. “My great-grandfather, Hans Borgwardt, immigrated here for reasons unknown. Could be sinister. I can’t call it. I really can’t. Bogwardt means castle watcher. It implies that my ancestors probably did groundskeeping, or maybe security guard duties.”

The Rad Race event that Devin participated in was called Fixed 42. “It’s all track bikes. Everyone’s got monster gearing. They closed the Autobahn for like five kilometers of it the last few years. There are 250 people, and it’s just full gas. There’s no neutral energy. Most races, you start, and it’s like, ‘We’re gonna settle in, we’re gonna see who’s doing what, we’re going to keep an eye out.’ This race is like, ‘Go.’

The start of this race is the most important part, because if you aren’t pushing hard out of the gate, chances are, you will not do well. “It is a 30 to 32 miles per hour average for the entire race, which is insane. That year, I was with the chase group just behind the lead group for about two-thirds of it, and I had a 29-mile-an-hour average with that group. The lead group that year was about 30 miles an hour.” Devin had an impressive start to this race, but the insane pace of the race proved to be a challenge in the latter portion. “My gearing was so heavy, and once you get under a certain cadence on a really heavy gearing, you’re fighting an uphill battle. It’s so hard to get it back up, especially when you’re depleted. I was gassed. Every time a group went by me, the last four kilometers of the race, I’d get up, I’d sprint, and I’d be like, ‘Okay, I’m gonna get in this group, I’m gonna get into their slipstream.’ It was a solo finish to that race because of that, but I was really happy I went. I was happy I gave it a go, and I was grateful to have spent some time at the very front of the race for a good chunk of it.”

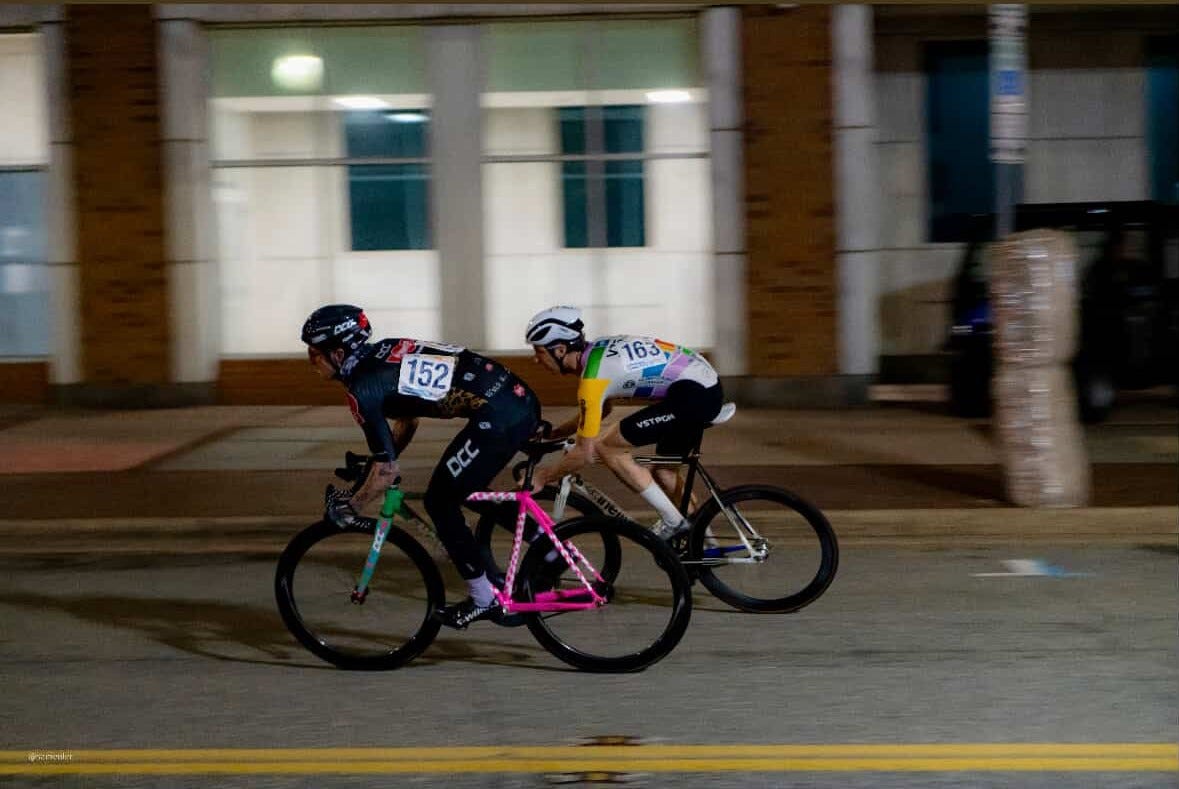

While in Berlin, Devin caught up with his friend Dex, the team director for D3stroy Cycling Club. During that conversation, Dex asked Devin if he wanted to be a part of the team. For the past two years, Devin has enjoyed racing for DCC. “Our main sponsor right now is Engine 11, and I’m very lucky to race for a team that’s sponsored by a frame company. It’s been wonderful. They’re a really inclusive team and they actually take a lot of time to focus on each rider, what our goals are for the year, and which races we’re trying to do. It’s a very loose structure in that as long as I’m on the team, there’s no pressure to do any amount of races.”

When he wasn’t racing, Devin made the best of his trip to Berlin. He enjoyed the laid-back, slow-paced environment of the city, compared to the United States. “Maybe I’m romanticizing it a bit, but visibly, there was less hurry there. There was less stress and more intent to just amble about.” The only drawback for Devin in Berlin was adhering to their strict rules. “Every red that I ran in Berlin, pedestrians were screaming at me. There were a handful of videos that I took, where I was cooking through really narrow roads, and there’s really good bike infrastructure there. All of my friends in Berlin were pretty immediately like, ‘You cannot ride like this here. They will arrest you.’”

Riding fast is more or less a non-negotiable for Devin, as it’s the element of cycling he enjoys most. “I like going fast. There’s something about taking a corner at 30 to 35 miles an hour on a brakeless bike where you could pedal strike that just does it for me. Something about that really butters my brain up.”

Devin’s tendency to ride fast has resulted in some negative consequences over the years. “I don’t exaggerate, and feel like I almost don’t talk about it because everyone is going to think I’m exaggerating, but I’ve been hit around 40 or 50 times over the last 13 years.” Among the high total of collisions Devin has been involved in, only two or three of them have been his fault, he suggested. One incident that stuck out in his mind happened in Florida, when a police officer collided with him. “She was like, ‘I didn’t hit you. I didn’t hit you.’ My wrist broke her taillight, I had to go in an ambulance. They twisted the words to say that I intentionally touched the car. They categorized the police report as damage to government property and called for 20 squad cars and four fire trucks. I’ve never seen so many first responders, and it was just because it was damage to government property.”

Devin recalled some other crashes, which he playfully referred to as, ‘smacks.’ He noted that, miraculously, his bike has suffered minimal damage from the crashes. “I shit you not, every time I’ve been smacked and I pick my bike up, my bike is fine. My tires and wheels are fine.”

Devin said that the craziest crash that he was involved in happened right before he moved out of Florida in 2024. “I was on this road where there’s no bike lane, and a state road intersects another state road. Each road is like eight lanes, and there are two turn lanes. I was taking a left across the two turn lanes as the light was changing.

The light turned red, I see a big red truck, I blinked, and I was flipping in the air. I landed on my ass. I picked up my carbon road bike, not a flat, not a scratch.” The truck hit Devin’s back tire at around 45 MPH, and amazingly, Devin walked away mostly unscathed. “There was a big stage because there were so many cars waiting. Multiple people got out of their cars. The dude who hit me stopped and turned around. He was really sweet. He was concerned. He didn’t even look at the damage to his truck, but he was like, ‘Can I take you home?’ And I was like, ‘I got places to be, and I was still going to ride another 20 miles, but thank you.’ He was really shook that I was okay.” Devin has experienced multiple interactions where he has walked away from an accident, perplexing the person who crashed into him. “It’s kind of comical to have these interactions with so many people where you can tell their mind is blown.

They’re like, ‘Oh my God,’ and then you just ride away.”

Devin’s wife, Amber, has frequently been there for Devin through his many crashes, and admitted that she would be surprised if his cause of death wasn’t related to a bike crash. Due to his high volume of crashes, Amber recently convinced Devin to wear a helmet, which he had previously opposed. “I’m not pro-helmet. Like, I think we should all be wearing helmets, but what bothers me is that I shouldn’t have to wear one with my proficiency on the bike. I ride a bike better than I walk. I have to wear it because everyone else is being selfish on the road. It really bothers me that we have to cater to our safety toward the people who are intentionally making it more dangerous for everyone else.”

Devin and Amber lived together for years in Florida, Devin as a coffee roaster, Amber as a hairstylist. Craving a change of pace, the couple moved from Florida to New York City in the Summer of 2024. “We lived a real calm lifestyle in Florida, almost like semi-retired, which is a big part of why we moved. I was sitting on my porch for five to six hours a day, just smoking weed all day, chilling with my cats. That was fun, and we would do that all over again, but we wanted more out of life.”

The couple decided to move to New York City after making friends in the NYC biking community on social media. “We wish we had done it sooner. I spent two years traveling there every month and a half with no plans, just lucky to have friends’ couches to crash on. Honestly, within just a handful of trips, this place felt so much like home. More than Florida ever did.”

Since moving to New York City, Devin has been involved in five separate crashes. There is one in particular that he finds comical to describe. “I was three blocks from our home in Crown Heights. It had been a few blocks in front of this police car with its sirens on, so I knew he was behind me. I was coming up to a road with a left-turn-only, so I passed the car on its right, and sure as shit, right as I was passing that car on its right, they heard the siren. It was this 18-year-old kid delivering prescriptions for his pharmaceutical job. He fucking jackknifed the tires. He drove up onto the sidewalk. He didn’t know what he was doing, but he yielded to the police car a minute before he needed to.”

In contrast to his collision with the red truck in Sarasota, Devin perceived this crash in real time. “I could see the curb coming, and I was like, ‘I’m gonna have to bail.’ I was going like 25. I was shirtless, and I was helmetless for summer. It took long enough for me to say, ‘I’m going over the bars.’ I got my feet out of the straps, I somersaulted maybe five or six times, and damn near landed on my feet, not a scratch. As soon as I was on my feet, I looked, and this old woman was sitting there. She goes, ‘You win!’ It was so funny.”

Devin didn’t exactly put the driver at ease when he exited his car to assess the damage. “The kid got out of the car and was having a religious awakening. He was talking to God and crying. I was not doing a very good job to reassure him. He kept being like, ‘This is gonna fuck up my life. I’m gonna lose my job,’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, you are probably going to lose your job.’ He kept being like, ‘I’m a terrible person.’ And I was like, ‘You’re just a really bad driver.’”

Devin used this experience to vent the frustration pent up from being hit by cars so frequently. “It was one of those moments where I really recognized it. I kind of looked at it like, ‘I’ve been hit so many times, and I am such a bitter — I’m just a grinch.’ I finally wanted to make someone understand the gravity of what they did. I told him that I lost friends to people who did what he’s done. I told him that if I was a normal person, if I was anyone else, I am the less than one percent of people who wouldn’t have died from that. I made sure that he understood he would have killed any normal person who didn’t know how to handle a situation like that.”

Regularly crashing his bike has taught Devin to brace properly to protect himself. “Somehow, my brain kicks in, and I’ve been able to tumble right, fall right, distribute weight right. I’ve had some bone breaks and muscle tears, but I’m real lucky to still be spinning my legs.”

Most recently, Devin suffered a broken heel as a result of a crash during the Summer of 2025. “I was crossing Atlantic [Ave] in the middle of the light change, and everyone had rushed in and it was gridlocked. As I was crossing the front of this old Hasidic guy’s car, he hit the gas pedal a little too hard, wasn’t expecting me, and just fucking threw me from the bike. I broke my heel in three pieces.”

Devin said that he blinked and the next thing he knew, he was sitting in the middle of the street. When he tried to get up, he couldn’t put weight on his left foot. He hopped over to a nearby gas station, where the driver offered sympathy. “He was really sweet and concerned about me. I was kind of like, ‘No, you can go. This wasn’t your fault.

You weren’t expecting me.” He goes, ‘No, no, no, You’re a person. Are you okay? He was intent on taking me somewhere, so I was just like, ‘I just want my wife.’ He took me home. Then we went to the hospital, and I was there for 14 hours. I was out of work and completely laid up for seven weeks.”

Being unable to walk for many weeks made life much more difficult for Devin, whose work and hobbies require two healthy feet. For work, Devin roasts for his own coffee company, Betrübt, and has a second job at Arcane in the West Village. “I’m on my feet for eight to 10 hours a day. I was only getting up one to three times a day for seven weeks straight, and that was really hard.”

Losing mobility and being unable to do the things he loves sent Devin into a self-described identity crisis. “Every time I’ve been hit, I’ve been really lucky. Like, on my feet after every injury, I usually have issues, and my wife has to help me with some things, whether it’s getting dressed, showering, whatever, but I’ve never not been able to ride a bike within a week of injury.”

Fortunately, Devin’s injuries haven’t negatively affected his spot on DCC. “The team director is a person. He’s not someone who’s like, ‘You need to race, you need to do this, you need to do that.’ It’s not all like expectations. When I was injured, his main concern was my injury, not when I was going to be back. As I’ve recovered and kept in touch with him, his main concern hasn’t been when I’m gonna be back, just that I’m doing okay.”

Having 40 to 50 bike accidents, varying in severity, begs the question: Why? At a certain point, wouldn’t one feel inclined to ride slower or put themself in fewer dangerous situations? “Sometimes I feel like I can’t be killed, which is so ironic because I’m also so at peace with dying.” Devin dropped this quote very nonchalantly, so I asked him to elaborate. “Contextually, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to look at me without speaking to me and say, ‘This is a sad person.’” For those who don’t know Devin, he is covered in several tattoos. One of these tattoos is below his right eye, and says ‘Betrübt.’ This is the name of his coffee roasting company, and it’s also German for ‘sad or upset.’

It’s not lost on Devin that the way he operates his track bike is extremely dangerous. “I’ve had so many moments where, even if just for a millisecond, I’ve said to myself, ‘Oh, this might be it. I might bang my noggin on the ground and not have a single thought.’ I’ve had a lot of moments, even where I haven’t been hit, where I’m going 30 plus miles an hour, and I shouldn’t have to be thinking about a car turning out from a side road, but I can see him inching. I have those moments where I’m like, ‘Oh, this is going to be a moment where we have a weird back and forth, and I finally get hurt.’ I’ve had to face that a lot.”

Ironically, being at peace with death comes from the fact that Devin has experienced the death of cyclists in bike-related accidents. “Whether I knew them personally or not, and I have known a handful really personally, I’ve lost a lot of friends in the bike community over the course of 13 years. I think maybe one or two of them was from running a red light. The rest of the many was from people who were just getting home. Part of me has continually found peace with the fact that I am a statistic already. Look at how many times I’ve been hit. I’m just the lucky statistic for now.” Although Devin has suffered these losses, he feels as though the fear button in his brain is broken. “I really don’t think I’m scared of cars, and I should be.”

When considering why he’s gotten into so many accidents, Devin explained that it typically happens when he goes against his instincts. That’s exactly what happened when he broke his heel. “I’m a very present, conscious person. I saw the gridlock, and I was like, ‘Maybe I should wait for everyone to go through, but then I said, ‘Nah, you’re good. They’re chilling.’ My big takeaway from that injury is that I have been listening to my gut more. When I see an intersection, and I can’t fully see what’s down the road or when I have that thought of, ‘I shouldn’t take that line,’ I’ve been listening to that.”

Devin explained that it’s important to commit to whatever your instincts tell you to do on a track bike. “If there’s one thing that I’ve learned, it’s that hesitation on a track bike is what hurts me. When you hesitate, you interrupt your intention, and you interrupt what it looks like you’re doing to anyone who’s watching. You mess up the natural flow of everything. So anytime I have a hesitation, I do respond to it.”

Despite following his gut to keep himself safe, Devin is still intent on running red lights and darting through traffic. “I love seeing a big hoard of traffic to have to be technical to get through. Living in New York has made me like traffic less than in Florida because the roads are narrower. Instead of thinking five steps ahead in Florida, you have to think 20 steps ahead here, but I still love it. It’s like a playground. It’s a big part of what keeps me going.”